Cornovii in 60 seconds

• Shropshire Council owns Cornovii

• Shropshire Council lends it money

• Those loans are secured on public land

• If Cornovii fails, the Council is on the hook

• The taxpayer ultimately carries the risk

We ask why that arrangement is still described as “arm’s length”.

They call it “commercial”.

They call it “arm’s length”.

Funny how every arm, hand and pocket involved belongs to Shropshire Council.

Why the Risk Never Left Shropshire Council

If Cornovii Developments Ltd were to fail tomorrow, which part of the risk would not fall back on Shropshire Council — and where, precisely, is it recorded?

It is a modest question. Polite, even. The sort of question one might expect a council to have asked itself before embarking on a multi‑million‑pound property adventure. And yet it hangs there, unanswered, like an awkward pause in a committee meeting chaired by people suddenly fascinated by their papers.

Cornovii Developments Ltd is routinely described as “arm’s length”. This phrase is delivered with confidence, usually by people who have never explained where that arm begins, where it ends, or whose arm it actually is. The paperwork, sadly, is less poetic.

The Council owns Cornovii.

The Council funds Cornovii.

The Council lends to Cornovii.

The Council holds legal charges over Cornovii’s assets.

At this point, the word “commercial” begins to feel decorative.

At what point does a council‑owned company, funded by council loans, secured on council land, cease to be “arm’s length” — and who signed off that conclusion?

One might reasonably expect such a conclusion to be documented. After all, this was not a back‑of‑an‑envelope experiment. This was a deliberate strategy, advanced, defended and overseen by senior figures — including Mark Barrow, former Director of Place, and elected members such as James Owen and, before him, Dean Carroll.

These were not innocent bystanders. They were the architects — or at least the people who stood confidently at the lectern while others assured them that property development was essentially just Lego for grown-ups.

The result is a structure in which risk has not been transferred away from the Council, but politely walked around the building and brought back in through another door.

For readers who do not spend their evenings reading company accounts, here is the plain‑English version.

If you lend money to yourself, using your own house as security, you have not reduced your risk. You have concentrated it.

Cornovii’s accounts show land, developments and work in progress worth tens of millions. They also show heavy borrowing, ongoing liabilities and a serene assumption that everything proceeds according to plan. That assumption has been endorsed repeatedly — often by the same small cast of characters, rotating between committee rooms with the confidence of men who will never personally underwrite the consequences.

Which risk in Cornovii’s accounts is not ultimately borne by the council taxpayer — and how would the public recognise it if it materialised?

If a development underperforms, who absorbs the loss?

If asset values fall, who takes the hit?

If sales stall, costs rise, or interest rates bite harder than forecast — where does that pain land?

Not with a private investor.

Not with an external developer.

But with the same council already explaining why libraries must close and grass will be cut “less often, but more strategically”.

What is most striking is not the ambition, but the silence.

There is no clear exit strategy.

No defined point at which exposure reduces.

No moment where risk is said to leave the public balance sheet.

Instead, there is reassurance. Repeated, confident, and curiously detached from the documents filed in black and white.

And so we arrive at the final question — the one that tends to end conversations rather than start them.

If the council owns the company, funds the borrowing, holds the charges, and absorbs the consequences — what, exactly, is Cornovii insulating the public from?

If Things Go Wrong

Two scenarios are rarely discussed.

The first is Cornovii going broke. In that case, the Council steps in — not as a distant shareholder, but as secured creditor, landowner and ultimate guarantor. The losses do not vanish. They crystallise.

The second is the Council liquidating assets to recover its position. That means selling public land, developments and sites once promised for “strategic benefit”, likely under pressure and at less than ideal value.

Neither outcome looks much like risk mitigation.

Both look suspiciously like the bill coming due.

One hopes this was all carefully thought through.

But hope, as history repeatedly demonstrates, is not financial control.

Postscript:

Some councillors have told me they’ve “seen the material” and simply don’t believe it. That is, of course, their right.

But where elected representatives choose disbelief over due diligence, the burden does not disappear. It merely waits — until the consequences require explanation rather than opinion.

This is not an argument against regeneration.

It is not an argument against building homes.

It is an argument for honesty about risk — and for stopping the pretence that shifting money between council-controlled entities makes that risk disappear.

It does not.

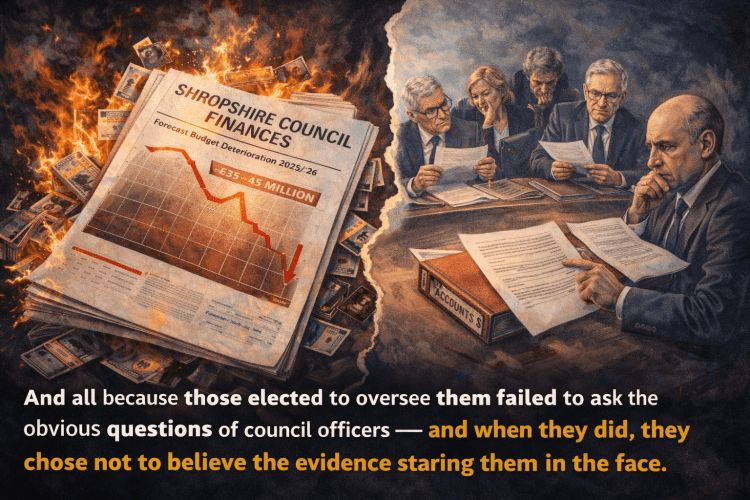

By the end of the 2025/26 financial year, Shropshire Council is likely to be managing a £35–45 million deterioration against a stable position — not through one failure, but through many quietly tolerated risks.

And all because those elected to oversee them failed to ask the obvious questions of council officers — and when they did, they chose not to believe the evidence staring them in the face.

So pleased that someone/ people are looking in detail at the goings- on at Cornovii Developments Ltd (CDL) and its parent body the Shropshire County Council. I thought that I was a lonely voice crying in the wind which led to me asking questions at the Shropshire Council meetings on 17 July and 11 December about finances, directors/ staff costs and the type of accommodation being provided by CDL.

I looked at the Council’s Strategic Review about the future of the now empty county Shirehall and guess what, CDL are being used in a large way (para 2.12) yippee!!!

Keep up the good work, whoever you are out there

Hi Andrew, Keep sending your views on Cornovii Ltd. Exposing these people to daylight is the one thing they hate.

Kind regards

LikeLike